Links and Things to Use in NYU and Other Classes

(A lot of this used to be my old handouts)

2022 new stuff not organized yet:

Philip Klay on how to write about war.

Jordan Kisner inThe Atlantic on failing to cross cultural divides in fiction (a review of Geraldine Brooks's Horse).

Department of Shameless Commerce: MSW is giving a private half day workshop by Zoom about writing the Scene on 1-15-22. Information here.

The New York Times, April 5, 2022

Reviewing REFUSE TO BE DONE: How to Write and Rewrite a Novel in Three Drafts (156 pp., Soho Press, paper, $15.95) by Matt Bell.

[Noor] Qasim writes: "Bell structures the book around what he calls the novel's three provisional drafts: 'generative revision,' 'narrative revision' and 'polishing revision.' .... The abundant first chapter, outlining the basics of the "exploratory" initial draft, is carefully elucidated, if admittedly all about 'chaos.' In the second and third chapters, Bell attends to structure and style, guided by two principles. The first: 'One should 'rewrite instead of revise.' How to tell the difference? 'The presence of new typing … and the absence of merely copying and pasting.' Second: One must simply 'refuse to be done.' Where a less capable teacher might leave us wondering how, Bell holds us accountable with an exhaustive list of editing approaches, from pulling up widows to reading aloud to identifying 'weasel words.'"

Do you need ideas for starting your novel? Check out MSW's article online from The Writer: "How to Get a Novel Started."

A close reading of a well-made first paragraph (Emily Temple on True Grit)

Authorspublish Newsletter Free and useful

Do-It-Yourself MFA

Deep Point of View (from Masterclass.com

Samples of Editing in a piece by Danny Williams called "Real Life Adventures in Editing"

Power Point Primer on book reviewing--a good primer.

Just for fun: Fifty-very-bad-book-covers-for-literary-classics/An article in Jane Friedman's blog about use of various types of third person in fiction.

Article in A Journal of Practical Writing: "Cultural Appropriation in Creative Writing.

On using the present tense: http://www.meredithsuewillis.com/materials.html#presenttense.

Two Authors discuss at NY TImes--"the bad art friend"

50 Really Bad Book Covers for Classics

Cartoons

Links to Articles and More

Marketing and PublishingMaterials by MSW to Read

Samples to Read

Online Materials and Links in Alphabetical Order

Action Writing (sharp shooting) from One Shot by Lee Child

Adverbs (from The Guardian)

Authentic Accents--from Writers Digest

- Archipelago Method

Beat Sheet

Best Seller: How to write one (James Scott Bell)

Ideas on Story and Structrure from Best Sellers

From James Scott Bell, a thriller writer and lawyer, has a course at the Great Courses on writng a best seller:

Bell focuses, unsurprisingly for thrillers and mysteries, on story/plot sources and then on structure: something he calls the LOCK system.

I. First, he suggests how to get a good story:

• What-If Moments: We all have crazy what-if thoughts that cross our minds from time to time. Likely, most of us simply just laugh them off. Try making the most of what-if moments. The next time you wonder, "What if this plant I'm looking at suddenly started talking to me?"—roll with it. What would it say? Would you talk back or run away? There is a story here.

• Weird Job Situations: Giving people insight into the daily life that only a few select people could provide can be a fascinating read. And putting your characters in jobs with tremendous tension helps keep your reader on edge. What does a day in the life of a bomb disposal technician look like? How does this person deal with facing death on a regular basis? Would she try to find love and start a family? There is a story here.

• Hear the Headlines: But don't go much further than the headlines. Work with just a limited amount of information and use your imagination to fill in the details. "Scientists Discover New Fish That Walks on Land." What would that look like? Do you go fishing or hunting? There is a story here.

• The First-Line Game. As Mr. Bell points out throughout the course, the first sentence of a novel is one of the most important. One good line can not only hook your reader into buying the book, it can hook you into a story you never imagined. Experiment with fun, funny, weird, cool, intriguing first lines and see where they take you. "Today I learned you should never travel to Jupiter without an extra pair of underpants." Who is going to Jupiter? Why underpants? Wait, WHAT? There is a story here.

Don't get caught up in the realities of our world, the illogic of your ideas, or the fear that someone might laugh. Audiences are eager to suspend their disbelief for a world that captures their imagination. It's just like Field of Dreams claimed: "If you build it, they will come." Remember, at some point, Michael Crichton wondered, "What if a mosquito that was stuck in a rock resulted in an amusement park full of real-life dinosaurs? There is a story here…"

II. His "LOCK" system provides structure as he sees it:

L - Lead: Your protagonist can be:

• positive—the hero, someone who embodies moral codes of a community, someone who readers root for;

• negative—does not adhere to the moral code, we root for them to change or to get their just desserts; or an

• anti-hero—has own morals, usually dragged into a community kicking and screaming. You want to bond your reader to your lead by putting them in a terrible situation, a hardship, or inner conflict to evoke sympathy or empathy.

O - Objective: Your lead has a mission: to get something or get away from something.

C - Confrontation: Ramp up engagement by pitting opposition and/or outside forces against the lead accomplishing his or her objective.

K - Knockout: Give your reader a satisfying conclusion that resonates. There are five fundamental endings to best sellers. You will probably recognize them from movies and television shows as well:

Lead wins, gains objective;

Lead loses, missing objective;

Lead loses objective, gains something else of value;

Lead wins objective, loses something of value;

or Open/ambiguous ending.Once you've locked in your LOCK, you have the start of a best seller.

"As Mickey Spillane noted, 'The first chapter sells the book. The last chapter sells the next book.'"

Books to Read to Learn to Write Novels

Creative Dialogue Tag Syndrome --An article on "creative dialogue tag syndrome" and what's wrong with it. (This is good, but I don't agree with all of it-- consider it one bossy editor's opinion, certainly worth hearing, but not the voice of God.)

Character, some notes on

Conflict

Critiquing guidelines

Critiquing continued:

Offer any expertise you have.

Separate line editing from conceptual editing

Writer should ask for specific kinds of critique

Be prepared to talk, but try not to repeat.

Write a holistic note;

use "comments" in Word

scan in and email.

Send by snail mail.

Crowd scenes

Some Tricks for crowd scenes:

Here are a couple of practical ways of dealing with logistics and large groups. I probably shouldn't talk about tricks-- all prose narrative, after all, is an illusion of reality-- but as you revise, you can try these things to make the story telling run more smoothly:

• Only identify two or three individuals in a scene. Say "The twenty two the Ridgewood Bobcats players walked into the dressing room with long faces," and then give quoted speeches only to Rob, Andre, and the Coach. The other Bobcats can mutter as a group, or lower their heads in shame, but they remain a mass, part of the scene setting.

• Only give proper names to the most important characters in a group scene. (As above. Be sure you really need the names. Proper names call attention to themselves.)

• Clarify the logistics and physical action by giving a firm point of view. Imagine a fixed camera or a character in a chair in the northeast corner next to to the white board. Write only what is seen from that point of view. This will help keep the reader oriented. If that point of view or fixed camera angle is blocked by a pillar, don't tell what can't be seen. Even if you have a multiple viewpoint story, write your action from one point of view.

• Conflate. If you are writing fiction based on you own real family, for example, conflate two annoying little brothers into one. It strays from the facts, but allows the creation of one full character and eases your logistical problems.

Cutting and Tightening

Dealing with Dialect/ DialectSamples

Description-- Extremely mini-lecture on description

Extremely Mini-Lecture on the uses of description

First: Concrete description is best, using the senses whenever possible. We best communicate in words what we see in our minds by sharing the lowest common denominator: red, warm, smooth, crisp, sweet, juicy. That is to say, sense details. It's not the only thing in writing, but it is essential for those of us writers (novelists and other fiction writers!) who aren't illustrating their work or depending on costume designers and actors to give the timbre of the voice, the fabric and folds of the cloak.

Second: Drafting lots of rich description will help you see your work more completely and clearly and may even give you ideas for new scenes, new characters, new depth! Over-write as you make your first draft.

Third: In your final product, cut most of the description you drafted. Make your descriptions as concise as possible, retaining only the very best details, See "The Lady Sheriff."

Description: Where to put it

Detroit--Elmore Leonard's crime novel Detroit:

Dialect Issues: Ed Davis's article in the Writers Digest's Blog about writing dialect.

- Dialogue and Dialect: Use and Misues

Use and Misuse of Dialect, Accents, & Foreign Languages--

What is the best way for a writer to show that a character speaks a particular dialect or with a particular accent? This is tricky, because there are serious pitfalls, namely readability, accuracy, and respect. As wonderful as Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is, there are passages that are very wearying if not unreadable because of the thick transcription of dialect:

"I got hurt a little, en couldn't swim fas', so I wuz a considable ways behine you towards de las'; when you landed I reck'ned I could ketch up wid you on de lan' 'dout havin' to shout at you, but when I see dat house I begin to go slow. I 'uz off too fur to hear what dey say to you- I wuz 'fraid o' de dogs; but when it 'uz all quiet agin I knowed you's in de house, so I struck out for de woods to wait for day..."

This is slow, painful going at best, and I'm not sure it's even truly accurate.

The fact is that, since narrative is always an approximation of speech, we are probably better off hinting at accents and dialects. We can never truly transcribe the exact sound of language.

Variations in word order and vocabulary tend to be richer than attempts at transcribing

pronunciation exactly. Occasional touches of non-standard grammar or a hint of pronunciation also go a long way toward creating the illusion of how a speaker speaks. Look at the opening of Denise Giardina's Storming Heaven (Denise Giardina left) which hints at an Appalachian dialect:

They is many a way to mark a baby while it is still yet in the womb. A fright to its mother will render it nervous and fretful after it is birthed. If a copperhead strikes, a fiery red snake will be stamped on the baby's face or back. And a portentous event will violate a womans entrails, grab a youngun by the ankle and wrench a life out of joint.

The written word is always an approximation, a created thing; the writer's job is to create a functional illusion. This uses certain Appalachianisms ("They is," "youngun") but makes no attempt to transcribe pronunciation. "Youngun" is treated not as standard English missing an apostrophe but rather as an Appalachian word.

Consider also what it means when you transcribe one character's dialect but not another's. For example, some writers use "in'" for "ing" in every word a character of Appalachian or Southern or African-American background says. In fact, very few if any dialects of English (and we all speak a dialect, even if it is Standard English) pronounce the full "ing." Jim's speech above in Huckleberry Finn, has "de" for "the," and again, this is a pronunciation toward which almost all English speakers tend, especially when they speed up their speech.

In writing dialogue in fiction, if you try to show every little variation from standard pronunciation for some speakers but not for every speaker, you are probably revealing what is at best at attitude of condescension.

Similarly, if you have passages where characters are speaking a foreign language, I like best to say it, in narration: "When they brought him in, his mother began to shout in Spanish." Then simply give the English, perhaps tossing a word or two of Spanish for flavor: "When they brought him in, his mother began to shout in Spanish. '¡Dios mío!' she cried. 'He's bleeding!'" This is not a perfect solution, and it is certainly not a rule, but if your objective is to move your story along with hints of spoken language, the one thing you don't want is to bring a reader to a full stop trying to figure out what language is being spoken or, worse, sounding out the words to figure out what they represent. Or going to a Spanish-English dictionary to figure out what the people are saying.

For more on these issues, here are some notes on using foreign languages in your novel and an article from Writers Digest that gives another point of view on writing dialect (that I don't totally agree with.)

Dialect Samples [Dialogue in Two Languages, Dialect Samples.

Dialogue in Two Languages

Dialogue Tags

Dialogue tags, Creative Dialogue Tag Syndrome . (This is good, but I don't agree with all of it-- consider it one bossy editor's opinion, certainly worth hearing, but not the voice of God).

Dialogue, proper (conventional) punctuation: The Two Lindas

Discourse, types of

Samples of Editing in a piece by Danny Williams called "Real Life Adventures in Editing"

Ediitorial marks.

Ellipsis etc

Epigraphs:

My current favorite opening line of a novel: "Frederick J. Frenger, Jr., a blithe psychopath from California, asked the flight attendant in first class for another glass of champagne and some writing materials."

Charles WIlleford, Miami BluesAnother good opening line: "Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr. Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months...."

-J.G. Ballard's High RiseQuirky quotation: "To all the devils, lusts, passions, greeds, envys, loves, hates, strange desires, enemies ghostly and real, the army of memories, with which I do battle—may they never give me peace."

-Patricia Highsmith, diary entryOld fashioned advice: "A novel should give a picture of common life enlivened by humour and sweetened by pathos."

- Anthony Trollope in An Autobiography

What kind of feedback do you find most useful? How do we evaluate fiction? What kind of feedback do you find most useful?

If you'd like, print out and use points for novel critiquing.pdf You can use this to give to people, as a guide, or not at all. You might also prepare your own form.

A couple of things to consider:

Separate line editing from conceptual editing

Offer any expertise you have--if you've worked as a volunteer EMT and someone has a scene with an emergency car, tell them what you think the got factually wrong.

To the writer: Ask for specific kinds of critique

Be prepared to talk, but try not to repeat.

Possible ways to make your resposnes:

Write a holistic note and email.

Use "comments" in Word.

Scan in your hand-written comments and email.

Send by snail mail.

Other Ideas?

Evaluating Presentation Pieces

Exercises to move your novel along

Flashback

Janet Burroway in Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft says: "Flashback is one of the most magical of fiction's contrivances, easier and more effective in this medium than in any other, because the reader's mind is a swifter mechanism for getting into the past than anything that has been devised for stage or even film....Nevertheless, many beginning writers use unnecessary flashbacks. This happens because flashback can be a useful way to provide background to character or events, and is often seen as the easiest or only way. It isn't. Dialogue, narration, a reference or detail can often tell us all we need to know, and when that is the case, a flashback becomes cumbersome and overlong, taking us from the present where the story and our interest lie.... "

Here are some materials on flashback

Flashback

the conventional story teller past, when you do a flashback, you begin in the past perfect tense (He had always gone to the Golden Dolphin after work...) and then after a couple of lines, you slip into the plain past again. This is an accepted convention of fiction writing, and it makes for vigorous story telling (He had always gone to the Golden Dolphin after work, but that day he went straight home...).

t gets tougher when you are in the present tense. The present tense is intrinsically inimical to the past: we usually write in present to keep the focus here and now. I'm not a huge fan, but more and more novelists prefer it.

Rule of thumb: if your story is in the present tense, once you've switched to the past, stay there.

But if you are writing in the past, start a flashback in past perfect and then slip back into the plain past

Foreign languages, putting into fiction

Formatting Fiction (The Two Lindas)

Formatting Fiction: paragraphs in Word

Gesture: Grandmother Eats

Gesture and Physical Action: Madame Merle & Geoffrey Clay father

Grammar--Tenses: Past Perfect (Pluperfect tense) from Grammarly Also see Grammar Girl/Quick and dirty Tips.

Grounding & Verisimilitude

Hero's Journey

"Homework" for Jump Start Your Novel (list of exercises to do on your own).

Homonyms

Illusion of How the Story is Told

Inner dialogue, how to write it. http://theeditorsblog.net/2012/02/28/inner-dialogue-writing-character-thoughts/

Interior Monologue: See "Inner dialogue.

Interiority: Anand Giridharadas on Interiority (NY Times Book Review in"By the Book" 10/16/22), iIn response to a question, "What moves you most in a work of literature?"

In my world of narrative nonfiction, interiority: the writer's ability to inhabit the character so that it is no longer just the character who is being described from the outside but also the world that is being re-described through the character's eyes."

Internal Monologue: Punctualing it

Joey looked at the two women posing as his long-lost cousins. Stupid ignorant fool. Should have known better than to hope..

Joey looked at the two women posing as his long-lost cousins. Stupid ignorant fool, he thought to himself. Should have known better than to hope...

Joey looked at the two women posing as his long-lost cousins. Stupid ignorant fool. Should have known better than to hope...

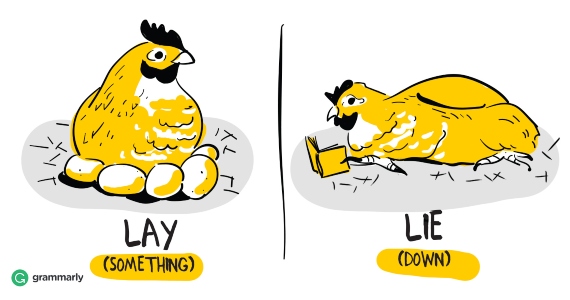

Mini-lesson on one of my Pet Peeves: Lie versus Lay

– Today I lie in my bed; yesterday, I lay in my bed. In the past, I have lain in my bed till noon.

– As we speak, I lay the paintbrush on the table. I laid it there yesterday too, and, in fact, I have laid it there many times.

– As we speak, I lay it down, and then the paintbrush just lies there.. But when I laid it down yesterday, it rolled off the table and lay on the floor.

Confused? Paintbrushes "lie" on the table or floor, but you "lay" the paintbrush down on the table. Then of course, it just "lies" there.

The really confusing part is the past tenses: "I laid the brush down beside the paints, and it just lay there." One verb has an object; one doesn't. Many, many people do this in a grammatically incorrect way.

For those of you who hate grammar and don't really care, take heart: there is an excellent chance that in another ten or twenty years, usage will have changed.

One current dictionary ( Random House Unabridged Second Edition) explains, "...forms of LAY are commonly heard in senses normally associated with LIE. In edited written English, [however,] such uses of LAY are rare and are usually considered nonstandard."

Mini-lesson on Lie versus Lay

– Today I lie in my bed; yesterday, I lay in my bed. In the past, I have lain in bed till noon.

– As we speak, I lay the paintbrush on the table. I laid it there yesterday too, and, in fact, I have laid it there many times.

– As we speak, I lay it down, and then the paintbrush just lies there.. But when I laid it down yesterday, it rolled off the table and lay on the floor.

Confused? Paintbrushes "lie" on the table or floor, but you "lay" the paintbrush down on the table. Then of course, it just "lies" there.

The really confusing part is the past tenses: "I laid the brush down beside the paints, and it just lay there." One verb has an object; one doesn't. Many, many people do this in a grammatically incorrect way.

For those of you who hate grammar and don't really care, take heart: there is an excellent chance that in another ten or twenty years, usage will have changed.

One current dictionary ( Random House Unabridged Second Edition) explains, "...forms of LAY are commonly heard in senses normally associated with LIE. In edited written English, [however,] such uses of LAY are rare and are usually considered nonstandard."

Logstics: The drunken Cowpoke Look at "The Logistics of Crowd Control Number II"

Logistics: more

Manipulation of Time in novels:

Then there is the manipulation of time, which novels do perhaps better than any other art form, using strategies like flashback, foreshadowing, and special techniques like ellipsis, summary, scene, stretch, and pause. We talked a lot early on about scene, which is the showing rather than telling of what is going on. I always speak of it as the quintessential building block of the novel. It is the central way we move novels forward, and I suggested that one way of drafting is to make rough versions of the 5 or 17 most important moments in the novel. This is the closest we write to real time. To stretch or pause time, on the other hand, allows us something all human beings seek, which is to stop and examine what is happening in detail, or to hold something that is precious or beautiful or powerful frozen for a while--or to get a second change, a do-over, a Take Two or Twenty two. One reason we write (even if it's fantasy or something ostensibly very unlike our own lives) is to get a new chance--to change what happened by going back in or stopping time.

Here are some more of the specific manipulations we use:

Flashback is not just "I remembered how we used to drink lemonade on summer nights," but when we stop the forward motion (the "present time") of our story and actually describe the flavor of the lemonade, quote what was said, write a whole scene that is as full and rich as a scene in the present of the novel.

Foreshadowing is useful in certain kinds of novels, often as a means of building suspense: here's the opening of Dennis Lehane's novel Live by Night:

Some years later, on a tugboat in the Gulf of Mexico, Joe Coughlin’s feet were placed in a tub of cement. Twelve gunmen stood waiting until they got far enough out to sea to throw him overboard, while Joe listened to the engine chug and watched the water churn white at the stern. And it occurred to him that almost everything of note that had ever happened in his life—good or bad—had been set in motion the morning he first crossed paths with Emma Gould.

Is Lehane manipulating us here ? Grabbing our attention? Sure, and we are pretty darn happy to be manipulated.

Memory, in its various forms, but especially when sense impressions usefully set off (and transitioning to) memories. (see Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu !)

Dreams and visions. To be used sparingly, but can be very effective in in novels becuase we engage the reader's mind and imagination.

Marketing and Publishing

Marketing Approches: Draft notes on getting published

Minor characters

The most minor characters of all are the thugs who attack the hero, the people at the biker bar--all really part of the scenery and best unnamed and described as "the one with the nose ring" or "a trio of drunk jocks." Describing them this way is, of course, stereotyping--it assumes things and turns people into things. This is more or less legitimate when you are setting your scene in a novel (although if the stereotypes are too obvious, it gets boring and stale).

Once the character moves from background to being a real person, however minor-- when the character gets a name or stands out even a little--then, in my opinion, the best fiction writers treat them with respect, however short their time on stage.

You do this, not surprisingly, by looking at them closely in imagination, seeing them in your mind with your senses as well as the part of you that generalizes. Perhaps even more important, this effort to see vividly and sharply gives you dividends: as you sharpen and individuate the minor character, new ideas for scenes and plot twists will likely come to you.

One way to help along with this process is to use lists like my "characteristics" to individuate and enrich minor (and major) characters. I think a list like this is especially useful for getting new material when you're stuck. If you give a couple of your characters a sign of the zodiac, for example, what could you do with that? Have a conversation about it? Maybe the hard-boiled detective thinks it's garbage, but suddenly he begins to see signs of the zodiac everywhere. Thinking about these things gives all kinds of new possibilities: thinking about your character's birth-order (baby of the family?) might suggest new behaviors. A mixed religious background (Dad was Jewish and Mom was Roman Catholic?) can give a myriad of ideas for actions and plot points. Even favorite foods could become important: she hates oysters and thus doesn't get sick when the group is served bad ones....

Monologue and minor characters

Now-- is it possible to write about it?

Order of Sentences

Order of information

Organizing Tip from Isabella Barrengos

Outlining: when to do it?

Outlining from Ten Strategies

Outline Samples and ideas:

Character Diagram Outline Timeline outline

Vision Board of a Novel using real-life materials to stimulate ideas

Suzanne's Excel outline for a novel in stories

Parts of a novel: None of these are required, but they are often used.

Prefaces and Introductions-- if you have a new edition you might write about what brought you to make these changes in your novel.

Prologue: this is a short chapter, usually a scene or narrative that precedes the time frame of the main story.

Epigraphs & quotations are sometimes offered as a kind of thematic statement or context for a novel or a chapter in a novel (George Eliot did a lot of chapter epigraphs).

Flashback is usually a fully dramatized scene from the past. They work best if they happen when something triggers the character to remember, and/or, when the character having the flashback is in a relaxed state.

Backstory is a narrated memory of what happened in the past of what happened to an individual character. In theater it isn't part of the play necessarily, but is one way an actor understands the character. In novels, it is often part of the story.

Flashforward or foreshadowing: large and small hints of what's to come. Most often used in a first person narrative where an older protagonist is talking about herself or himself as a younger person and gives something about the future.

Other things that are occasionally used: Cast of characters, family trees, list of sources for historical novels of very scientific science fiction.

Physical Action: The Godfather

Point of View Chart

Point of View examples

Point of View Problems

Point of view problem : The Kilted Warrior

Point of view problem: "The Thriller Bar Scene."

Present tense.

Prompts

Query Letter Samples

Quotidian scenes and objects to put in your novel

Process and Product: Click on "Read an Excerpt"

Real life and Fiction (Kidney transplant story)

Research for fiction: an article by Jake Wolff with about doing research for fiction.

Revising novels: Seven layers article ; Eight Final Revision Steps Before You Submit by Matt Bell. ; one page list of novel revision suggestions.

Revision of a passage: Tyler's New Clothes.

-- Tyler's New Clothes First version to second version: I just tightened. It's what I think og as soft,squishy sentences getting tougher and more wiry. . By the thiord, I was also making changes about what information is conveyed: information about the school, and the vice-principal. The original version has two women teachers talking naturalistically, but doesn't go very far with the story. I was still in my mind just listening to how they talked, to the relationship between the narrator and Fredda. It was about what can be observed on the surface. By the third version, I had what I wanted about the narrator and Fredda in other places. The final version, with the narrator and the vice-principal, is exploring a new character, the veep. It has more about the culture of the school.

I get tremendous pleasure in seeing the story come into view like this, like an old fashioned developer bath for photos. Another way I think of this is as sculpture: I get that elephant's general bulk hacked out, then the details that come into view.

Revision and Cutting: 2020 Cutting examples page

Revision of Tenses

Scene

Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important?

Scene: Material online

Seven layers to revise a novel article

Smirk--Smile in an irritatingly smug, conceited, silly or evil way.

Structure Your Novel Worksheet

Structure/Organizing idea from Isabella Barrengos

Switch Back Time:

https://keepswimming.online/2020/01/21/switchback-time/

https://atnesoiac.wordpress.com/2010/09/18/the-art-of-time-in-fiction-part-2/

Tags in dialogue; Creative Tag Syndrome;

Tense in Flashback

The conventional story teller past, when you do a flashback, you begin in the past perfect tense (He had always gone to the Golden Dolphin after work...) and then after a couple of lines, you slip into the plain past again. This is an accepted convention of fiction writing, and it makes for vigorous story telling (He had always gone to the Golden Dolphin after work, but that day he went straight home...). t gets tougher when you are in the present tense. The present tense is intrinsically inimical to the past: we usually write in present to keep the focus here and now. I'm not a huge fan, but more and more novelists prefer it.Rule of thumb: if your story is in the present tense, once you've switched to the past, stay there. But if you are writing in the past, start a flashback in past perfect and then slip back into the plain past

Example:

"She sat sewing lace at the neckline of the gown she'd worn when she'd married my father." The second past perfect tense is not necessary: by convention, in novels, once we've established the "past of the past," we can proceed in normal past tense: "She saw sewing lace at the neckline of the gown she'd worn when she married my father."

A thought on revising the tense in a first person y.a. novel. I originally wrote:

I had already decided I wasn't sticking around Hawkinsville for long.

This careful use of correct tense slows things down; more importantly, it takes off stage an important decision the character is making. During revision, I changed it to

I decided I wasn't sticking around Hawkinsville for long.

This is very small, but it adds directness, which is appropriate to this character. It moves the narrative toward dramatizing rather than relating, and even moves the passage along a continuum from narrative toward scene. It isn't a scene, but moves in that direction.

Terms for Novel Writing

That, using properly:

Using "that" in clauses: I always think of "that" as formal and probably unnecessary, but there are definitely times when it is needed for clarity: The mayor announced June 1 the fund would be exhausted. Is the mayor making the announcement on June 1 or will the fund be exhausted on June 1?

In a lot of fiction writing, you can cut it--it's how people speak. It's never incorrect, but sometimes wordy (here's a page online that discusses it nicely: https://web.ku.edu/~edit/that.html).

Thiird person in fiction, types of, from Jane Friedman

Tightening and cutting

Time in Fiction: Highly recommended: Joan Silber's book, The Art of Time in Fiction (St. Paul: Graywolf, 2009).

Types of Novels

Using Real life in your fiction: the Kidney transplant story

Verisimilitude & Grounding

Wedding Scenes: Best Wedding scenes Prose from Penguin UK!

Word: spacing between paragraphs in Word.

Writers Groups: Listed by region-- Writers' Peer Groups.

Yonnondio

A Novel Organizing/Structuring "Trick"

Isabella Barrengos

Reformat your novel in your printing settings -- select the options to print two pages per sheet and to print horizontally (make sure to number your pages)

Lay out every page on the floor (preferably somewhere with a lot of space and no open windows/air vents otherwise your pages will move around!)

Gather different color sticky notes and decide what themes, sections, structures you'd like to study in your revision:

– Major plot points

– Major turning points for characters

– Flashbacks

– Time jumps

– POV changes

Assign a color to each thing you'll be highlighting and put the sticky note on the pages where you see this pop up Step back and visualize!

You can also write directly on the pages, highlight large swathes, etc. Do whatever helps you see the overall arc of the story, where there might be lulls, where things might be happening too early or too late etc.

Links to Articles and Other Useful Things

Deep Point of View from Masterclass.com

A close reading of a well-made first paragraph (Emily Temple on True Grit)

Reedsy.com for free lessons and information on hiring publishing specialists (and more)

How some contemporary writers revise (from Lit Hub).

Grammar Girl

Malcolm Gladwell on the four types of detective/mystery.thriller novels.

Read this on Story, Plot, and Character: Dennis Lehane appreciates Elmore Leonard

"Stakes" Method of Outlining

Poets & Writers has a $4.99 Downloadable Book about the Process of Publishing

Interesting ideas from Alexander Chee on how he writes his novels

Alexander Chee on how he writes his novels

Here's a link to an article about a former NYU novel class student Marlen Bodden who has done well with self- publishing: https://www.pw.org/content/the_savvy_selfpublisher_marlen_suyapa_bodden

You'll notice she puts a lot of resources into the process-- her own money and time among other things. ]An article by Jake Wolff with about doing research for fiction

A critique of the workshopping with a silent author by Beth Nguyen

Piece about getting early readers for your manuscript: don't miss the section on special "sensitivity" readers and the responses in comments!

The Raised Relief Map-- a drafting technique for creative writers

Check out Harvey Chapman's Novel Writing Help. He's an oddity who seems to me more interested in how fiction works (and teaching it) than in writing it. He has a gruff self-consciously masculine style, but is definitely worth a look.

DIY/MFA?? Check it out!

Marketing and Publishing

1. Intro:

Today is a time of great flux--lines weakened between commercial publishing and so-called indie publishing (sometimes self-publishing, sometimes hybrid or subsidized or cooperative publishing). There are many models for publishing today, but making a living at it is less and less likely.

Returning to the Chaucer/Shakespeare/Jane Austen models?

There is a great deal of competition for the entertainment dollar!

The ideal, which I came in at the very end of, is that you get a literary agent who takes on book, sells to editor, who sells to her publisher, who edits, prints, sells, etc. You market your work to the agent (very genteely!), then the business is taken over by professionals. You were not really expected to "market" the finsihed product--maybe an all-expenses paid book tour.

This is still possible for a few, especially for nonfiction and for very commercial fiction.

Now, however, even with commercial publisher, authors are usually asked for a "platform" and sometimes to pay for their own copy editing and publicity.

"Independent" publishing has replaced "self" publishing, and it is not looked down upon nearly as much. It probably should not be your first choice though.

Note: even when I had a hotshot agent who placed my first novel with Scribner's, I placed my children's and literary short story book on my own. Agent just went over contracts and took her cut. Since my first three commercial novels, I've published with

another major New York publisher (children's novel)

several small presses that pay little or nothing

university presses that don't do advances, but do pay royalties

a cooperative press where writers share work and pay their own expenses

The world of e-book publishing without hard copies is a whole other kettle of fish: E-publishing is amazingly cheap, with often amazingly bad writing, and, especially with certain genres, has become a common outlet.

2. Give your first energy to getting your story and the words it's written with in excellent condition.

3. Then, as you approach publishing, do some research.

Check out these Draft Notes on Getting Published

For an excellent outline on the basics of getting published, look at Jane Friedman's page. You may also subscribe to her blog.

Best general resources on places to submit, lists of writing programs and conferences and much, much more: NewPages.com.

Also excellent site for general information (literary agents, for example,)is Duotrope.com.

MSW's Resources for Writers has a lot of odds 'n ends.

Especially for literary writing, see Poets & Writers.

Notes on various types of publishing at Publishing Types and Print on Demand.

How long should a novel be? See notes on my Resources for Writers page.

A one-pager, somewhat out-of-date, of resources about getting published

See blog post by Veronica Sicoe on why she self-publishes and

A Wall Street Journal article about Marlen Bodden, a former student in one of my novel classes who first self-published-- and then had her book picked up by a commercial press. Note: self-publishing should never be you first choice, but it should be on your list of possibilities.

Another good resource: An online magazine called AuthorsPublish at https://authorspublish.com/ . Here's their free guide to traditional-style publishers who don't require agents.

4. Do these things as you feel ready to market your novel

First, get the manuscript in pristine condition--editors don't have patience for mess and mistakes. The competition's too great.

Experiment with submitting to online journals, magazines, & contests--short stories or novel-parts, or sections of your novel that can be edited to stand alone. This can be useful when you try to get an agent or editor, evidence that someone else appreciated your work. There are infinite possibilities on the Internet and also look at NewPages.com. Most online and other literary journals don't pay. They are, however, easy to submit, using something called "Submittable." Note also that many of them charge a reading fee of $3 and up.

On Facebook, search for "Calls for submissions (poetry, fiction, art.)" Sign up to get notices.

Peruse old standards like Writer's Market and The Writer and Writer's Digest and get on Jane Friedman's free newsletter list.

Read Jeff Herman's Guide to Agents.Lots of good stuff, oriented toward literary writing, at Poets & Writers.

Consider going to a writers' conference to make connections and learn more. Some people love these, but even if you don't, one conference should give you an overview and the vocabulary you need to proceed. And doing no writers' conferences is just fine too.

Extra Marketing materials: Some repeats above

There is also the whole world of ebook only publishing, which is amazingly cheap. What is not certain is making much money at it.

There is a great deal of competition for the entertainment dollar!

Some specificrt marketing questions:

Once you feel your book is ready, what are the steps to getting it published?

How do you find an editor?

How do you find an agent?

How should you approach the above? What should you say in your cover letter?

What is the best way to ensure that someone in publishing will actually read your manuscript?

How do you copyright your novel to prevent someone from stealing the ideas and content?

Would self publishing be an option rather than go through all the rejections unknown writers are likely to receive? If so, are there companies you can recommend?

If you do get published, what rights should you negotiate?

Some sources suggest no major publisher will look at manuscript that is not supported by an agent? Is that true?

Are there good sources, a good list available, at places other publishers? clearinghouse?

What is the best way to track when publishers that are closed, open for submission again?

What are the most important aspects of the pitch letter, and are there tools that work better?

What is the right number of agents to query at one time? They take so long, and not all of them even reply. Is there any reason not to send to a hundred in one gulp?

In the notes about one agent, she wrote please, please not to send her stories about "white dudes on quests." That covers a lot of ground. I am all for diversity but still hope to be published. Any advice on how to negotiate this variable?

How on earth does one navigate these times relative to getting published?

Is it wise to have one's novel professionally edited before submitting a manuscript or wait for them to hand it to in-house editor?

How are publishing houses doing and what adjustments will they have to make now?

Are any of them actually making efforts to market one's book or is it up to the author to manage everything?

Some Questions:

(spring 2022)

From Jo:

1. Are there terms we need to know when talking with publishers, or editors?

2. Are marketing kits helpful?

3. Do today's writers market their work at conventions?

4. Can you recommend a website that has helpful marketing materials and information?

5. How did you publish your first book, and those that followed?

6. Would Suzanne be willing to share her experience with marketing and publishing her work?

From Philip

Would it help to hire a top public relations firm to help promote the sale of

your novel effectively to the public?

From Jody

Do you mean marketing in the context of positioning your book so as to gain an agent and then a publishing deal?

When I hear the word marketing, it denotes to me that which happens upon distribution being secured, be it a film or a book. But it would seem you are referring to that which the unpublished novelist can do to help secure interest from industry?

The same happens with indie film, in a way, but that normally involves a festival premiere and related positive publicity generated, as well as some social media presence. Is the book world the same? Are there noteworthy festivals or forums for unpublished writers and work that help garner attention to then hopefully attract lit agents et al.

From Tracy (2021)

" I would be interested to know how to find publications (paying if possible) where I can submit short stories to get my name out there."

From Clea:

1) I am interested in learning more about the role of an editor. How involved are editors? What is the process of finding an editor whom one works well with? Are they assigned by a publisher? Is there ever a situation in which one can submit work, without an editor?

2) Publishers: How does one go about finding a publisher? What are the steps, what is the protocol? And once one has a publisher, how does the process work?

3) And what is the agent's role in all of this?

From Philip:

Do aspiring writers have to be represented by a literary agent?

From Suzanne:

On author bios in cover letters for literary publications--should study at workshops be included or just MFA study?

If no MFA, should only publications where work was accepted be listed?

Is it critical to have a substantial resume of past publication by well regarded literary journals before approaching an agent for a novel or is the query letter with the pitch more important?

How many times would be reasonable to submit a story and have it declined before shelving it or doing a major revision?

From Dreama:

How about the effects of the pandemic? I have not been in a hurry to publish since the pandemic began.

She recommends MSW's website on publishing (Resources for Writers)

My local Virginia Writers Club has had a speaker who makes tons of money on Amazon. It's the subject: fantasy.

My best markets: teacher groups, library, and book stores.

From Alison:In attending the Algonquin NY Pitch Conference last spring, (virtual) several people were advised not to even mention past publications if they performed poorly in the marketplace. Re having short stories published, is it best to go for quality or quantity? Polish fewer things and aim for better journals/ magazines, or have more pieces accepted by less prestigious publications?

Other questions from past classes:

How do you copyright your novel to prevent someone from stealing the ideas and content?

Go online to http://www.copyright.gov for the latest information. HOWEVER, from the moment you finish a piece of writing, the government recognizes that only you can decide how to use it. The law presently governing this is the copyright law of January 1, 1978. A piece of writing is copyrighted the moment you put it to paper. You may indicate your authorship with the word Copyright (or the c sign), the year, and your name, but this is not necessary. Protection lasts for your lifetime plus 50 years. If your work is anonymous or pseudonymous, protection lasts for 100 years after the work's creation or 75 years after its publication, whichever is shorter. None of this holds in the case of writing-for-hire. You do not have to register your work with the Copyright Office to receive protection. If you want to, however, you may request the proper forms from the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559.

Would self publishing be an option rather than go through all the rejections unknown writers are likely to receive? If so, are there companies you can recommend?

What is the right number of agents to query at one time? They take so long, and not all of them even reply. Is there any reason not to send to a hundred in one gulp?

In the notes about one agent, she wrote "Please, please don't sent stories about white dudes on quests." That covers a lot of ground. I am all for diversity but still hope to be published. Any advice on how to negotiate this variable?

How are publishing houses doing and what adjustments will they have to make now?

Are any of them actually making efforts to market one's book or is it up to the author to manage everything?

Verisimilitude and Grounding

Verisimilitude is something I find myself querying in your home works and presentation pieces. The word does not mean "realistic" or "natural." Rather, it's whatever it takes to make a reader believe what they are reading. It means "the appearance of reality." In other words, does the illusion work? Does it seem true? Does the character seem 15 years old? Does she really seem like someone who has been homeless for two years?

Some very quotidian things readers usually need are things like characters' ages; what the characters look like (this can be very minimal--"with his long greasy red hair"; what century or world we are in. You may be quite general here--"Long ago and far away"-- and you may choose to leave a lot of uncertainty. The issue is to keep the uncertainly intriguing--how to tie it just close enough to something concrete so that the reader doesn't drift off to, say, the t.v.

Pacing is one of the trickiest parts of creating verisimilitude. Most of us just depend on our experience as readers to know how long a scene should take or how much to include, but as you revise, try to be thoughtful about your illusions. Sometimes it is enough to say, "Ten years passed...." Or, at the end of a struggle, the hero gets knocked out, there's some white space, and he wakes up and tries to figure out where he is.

More difficult is figuring out how long the struggle should go on to make it seem real but also to give an overview of what is happening. You want it to be very clear what is happening even if the character is drugged or confused! Good luck with that...

Verisimilitude is closely related to what we've been calling "grounding," which has to do with putting the reader's feet on the floor of a particular decade or distant planet. In my science fiction books I have (not terribly originally) made the planet have two suns, one pink and one blue. This makes me conscious of what color the shadows in the desert are, and this in turn helps keep me on that planet in my story and imagery.

In a novel I wrote that takes place in part during the second world war, I did a little light research with a box of crumbling newspapers at my mother's house. I found a nineteen forties newspaper and, since I'd given the main character a job in a movie theater, I thought I could find what movies were playing and what movie stars. She was a teen-ager, and the movie stars gave me the idea of comparing the stars to the real men and boys in her life. around her. So my research, slight as it was, helped develop character and story line as well as getting a few facts straight. It gave me more: I found an ad for a brand new floor model radio that I added to the décor of an affluent family's house. I also was reminded that women (and men) in the 1940's wore hats! Not only did people wear hats, but women were indulging that year in a style called a "picture hat" which had a huge round rim that was supposed to show off your pretty face. This gave me a scene in which the main character has trouble getting into a car because of her hat.

This is small stuff, but small stuff is precisely what grounds your reader. The things we touch and eat and sit on and wear are for novelists also what fuels our imaginations. It doesn't matter where the details come from, but if you don't have them, the grandest architectonics and the most gripping plot will feel sketchy and incomplete. The world of your novel will feel like someone's personal fantasy rather than a vivid fantasy world we can all imagine being part of.

A Physical Action Writing Assignment

Set a timer for 3 minutes. Write about a character in your novel running. If you don't have such a scene, add one--maybe from the part you haven't written yet.

The character may be fleeing danger or trying to make a plane or in a competition or playing with a pet. Write for 3 minutes seeing the action from the outside, concentrating on the movements and sounds, possibly using the screen technique above.

Set the timer again for 3 minutes. Write it from the inside. Concentrate on what the running feels like: feet pound? Lungs burn? Does the person fall?

Physical Action The Godfather

Writers who are naturals at dialogue and brilliant at structure and metaphor often have difficulties when their characters need to make a sandwich or kiss their lovers or strike out in a softball game. People write physical action in many ways, but the default is to describe it cleanly and smoothly, so that a reader can visualize what's happening and not have to get into trying to figure out whose fists smashed whose nose.

It is not as easy as it seems.

Here's an example that is plain and brief and cinematic in its small way. It was, in fact, transferred almost gesture by gesture to film.

The Don, still sitting at Hagen’s desk, inclined his body toward the undertaker. Bonasera hesitated then bent down and put his lips so close to the Don’s hairy ear that they touched. Don Corleone listened like a priest in the confessional, gazing away into the distance, passive, remote. They stayed for a long moment until Bonasera finished whispering and straightened to his full height. The Don looked gravely at Bonasera. Bonasera, his face flushed, returned his gaze unflinchingly.

-- Mario Puzo, The Godfather, p. 30

Love that detail of the hairy ear.

In general, physical action-- whether making tortillas or running for a bus or slashing with a knife, whether about making love or committing a murder-- works best when it is simple and sharp. The fewer words the better. Obviously this is a rule that has been broken often and to good effect, but start by trying to transfer what you see in your mind simply and clearly to the reader's mind.

One excellent technique to help you do this is to close your eyes and actually visualize a movie or TV screen. Watch your characters do their actions on the screen, and then write what you saw. Keep in mind that once again we are talking about revision, not drafting: I don't care how bad your description of action is in your first draft. Get it down first, then make it better.

Here are two passages of action. The first one is, which you are welcome just to skim, is a classic not-so-artistic passage of action from an old cowboy novel. It feels long and loose now, but Louis L'Amour was extremely popular in the last century

The second one is rather poetic, but also very easy to visualize. It also is about the narrator's experience, and and her feelings about dance and her dance teacher.

A Fist Fight from an old Louis L'Amour Novel

He Goes She Goes

Logistics

Action writing is the close-up, with details of the human body in motion. Logistics is about movement too, but it is the movement of large groups of people or things, or about people moving through space. Like group scenes, the multiplicity of moving parts makes this difficult to get right.

Read these short passages, examples of logistics and crowd control.

The first one is a newspaper account from the 1930's that attempts to describe something that was new at the time: air attacks on civilians. It is about an event that Picasso made famous in his monumental painting Guernica.

The second one is two versions of someone coming into a bar. One is written to give the layout of the room in a more-or-less cinematic way. The character scans the place and gives us a sense of what is going on, who is standing where. The second version has a vertiginous effect. Things are seen out of order. It is a point of view that shows the character is under stress or possibly drunk or drugged.

The final passage is from one of my novels, Oradell at Sea. I was attempting to do a little of all that: make the big picture of what is happening clear, but also limit what we see to what the main character sees. It's set in the dining room of a cruise ship. (Is anyone every going to go on a cruise again??).

Quirky quotation: "To all the devils, lusts, passions, greeds, envys, loves, hates, strange desires, enemies ghostly and real, the army of memories, with which I do battle—may they never give me peace."

-Patricia Highsmith, diary entryOld fashioned advice: "A novel should give a picture of common life enlivened by humour and sweetened by pathos."

- Anthony Trollope in An AutobiographySome Notes on Character

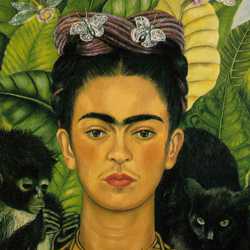

Frida Kahlo, who made a character of herself in her art; a scene from movie version of Hemingway story, "The Killers;" Fan-fiction characters

Character is generally easier to talk about with minor characters, which is the point of focusing on minor characters as an assignment. Your main character or characters are so thoroughly at the heart of your novel that their characteristics often form the very structure of the book, Does your character go from clueless and arrogant to wiser and more humble? (Jane Austen's Emma and the old nineties film version Clueless). Almost all the many coming-of-age stories including fantasy versions are structured like this--the changes in the main character shape the novel.

Minor characters, on the other hand, are more an essential part of revision. The most minor ones of all- the thugs who attack the hero, the people at the biker bar--are really part of the scenery and best unnamed and described as "the one with the nose ring" or "a trio of drunk jocks." Describing them this way is, of course, stereotyping--it assumes things and turns people into things. This is more or less legitimate when you are setting your scene in a novel (although if the stereotypes are too obvvious, it gets boring and stale), but once the character moves from background to being a character, however minor, when the characteer gets a name or stands out even a little--then, in my opinion, the best fiction writers turn them into real people, however short their time on stage. You do this, not surprisingly, by looking at them closely in imagination, seeing them in your mind with your senses as well as the part of you that generalizes.

Perhaps even more important, this effort to see vividly and sharply gives you dividends: as you sharpen and individuate the minor character, new ideas for scenes and plot twists will likely come to you.

One way to help along with this process is to use lists like my "characteristics" to individuate and enrich minor (and major) characters. I think a list like this is especially useful for getting new material when you're stuck. If you give a couple of your characters a sign of the zodiac, for example, what could you do with that? Have a conversation about it? Maybe the hard-boiled detective thinks it's garbage, but suddenly he begins to see signs of the zodiac everywhere. Thinking about these things gives all kinds of new possibilities: thinking about your character's birth-order (baby of the family?) might suggest new behaviors. A mixed religious background (Dad was Jewish and Mom was Roman Catholic?) can give a myriad of ideas for actions and plot points. Even favorite foods could become important: she hates oysters and thus doesn't get sick when the group is served bad ones....

The beauty of novel writing to me is that anything can be of use. The smallest detail can grow into something important. We get to use everything including the kitchen sink.

Tense Revision

This is from a first person YA. novel. I originally wrote:

I had already decided I wasn't sticking around Hawkinsville for long.

This careful use of correct tense slows things down; more importantly, it takes off stage an important decision the character is making. During revision, I changed it to

I decided I wasn't sticking around Hawkinsville for long.

This is very small, but it adds directness, which is appropriate to this character. It moves the narrative toward dramatizing rather than relating, and even moves the passage along a continuum from narrative toward scene. It isn't a scene, but moves in that direction.

Samples to Read

30th of July

Action: Sharp Shooting from One-Shot

Alice

Caddy JellybyCharacter description: Mr. Slope, Dave Rivers etc.

"Character-istics"

"Consultation" by Ariel Dorfman.

Dialect samples

Momaday Shoes

Night of the Hunter scene

"Old Florist" (poem);

Opening of Great Expectaitions

Tyler's New Clothes from Saviing Tyler Hake (tightening)Yonnondio

Huck Finn and Winterson

A Man Told Me by Grace Paley: A dialogue within a monologue

The Death of Mrs. Ramsay from To the Lighthouse.

Materials by MSW to Read

- Seven Layers to Revising Your Novel ( from The Writer Vol. 125, Issue 11)

"How to Get a Novel Started."

notes on forming a peer group.

Writing prompts, if you want them: I keep a long list on my website, and recommend them for re-starts or group writings.. Here's a sample.

Illusion of how the story is told

MSW on Dialogue

Cartoons

In class assignments and homework:

-- Put some religion in your novel– serious contemplations, or mentioned just in passing, maybe in dialog, or character passes a house of worship or a Mitzvah tank (do they still have those? Maybe a Chabad house)

Put a head covering into your novel (hat, baseball cap, hijab, battle helmet) into your novel. Focus on what the head covering looks like, texture, temperature even odor? Does it bring up a memory? Is it part of the plot? Does it change what happens?

Some NYU business links

2021

Academic Director the Center for Applied Liberal Arts Noncredit Programs Jenny McPhee ( jm279@nyu.edu); and/or Director of Writing Programs Abby Mack (abby.mack@nyu.edu).

Non-Evaluative credit: please see the attached form. Send it by e-mail to kf38@nyu.edu.

.jpg)